Part 3 of 3: Unification of the Italian Republic

It is rather remarkable that Italians across the country sang Bella Ciao in unison on Liberation Day, April 25th. To fully understand why this sense of unity moved so many of us, it is important to understand the slow and complicated process of the unification of the modern-day Italian state and its three most important players: Garibaldi, Cavour and Mazzini.

Italy was first united by Rome in the third century B.C. The territory remained unified for over 700 years, as a de facto extension of the capital of the Roman Republic and Empire, experiencing a privileged status even after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Following the conquest of the Frankish Eernance of Italy as a state. Italy gradually devolved into a system of city-states: Southern Italy governed by the Kingdom of Sicily – or Kingdom of Naples – and Central Italy was governed by the Pope as a temporal kingdom, the Papal States.

Mindsets shifted when Renaissance writers such as Dante, Petrarch, Machiavelli and Guicciardini started expressing opposition to foreign domination. Italy was thus divided into many small principalities, and it would remain that way until the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789.

During the French Revolution, 1789, Napoleon Bonaparte rose to power and proceeded to conquer the Italian states under a single administrative unit of the French Empire. He thus imbibed the ideals of the French Revolution which promoted liberty, equality, fraternity and strengthened the people’s participation in the political process. The Napoleonic Civil Code was created which united much of Western Europe under a unified system of clearly written and accessible law.

However, Napoleon’s power was shaken by the Napoleonic Wars. Napoleon’s reign began to fail and the ally national monarchs Napoleon had installed tried to keep their thrones by feeding those nationalistic sentiments, setting the stage for the revolutions to come.

The Battle of Waterloo marked the end of France’s rule over Italy and the return of monarchies. Anglo-Prussian forces defeated Napoleon in Waterloo in present-day Belgium in 1815, causing Italy to fall under control of multiple other nations. However, the ideas introduced in Napoleon’s rule remained.

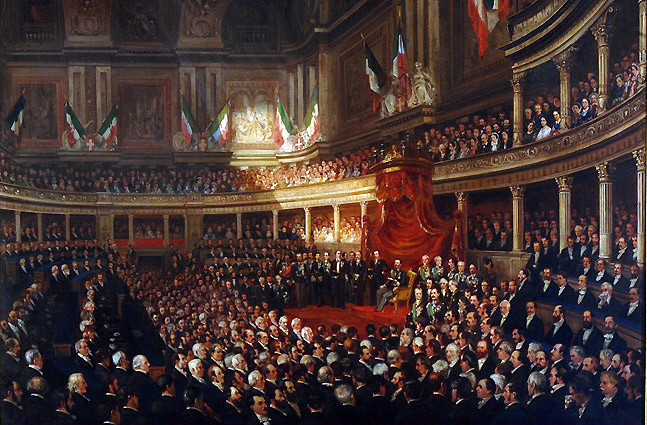

The Congress of Vienna in 1815 aimed to restore Europe to its former position, reversing the effects French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. Previous rulers were restored, and Italy was once again divided into numerous states: the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, the Duchy of Parma, the Papal States, and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies – fused together from the old Kingdom of Naples and Kingdom of Sicily. The desire for Italian unification increased even more than before.

During the Revolutions of 1848, Italians voiced concern over inefficiency of the Italian state created by the Congress of Vienna. Problems included: famines from crop failures, lack of employment, lack of necessities, and an idle and stubborn ruling class. Secret societies formed to oppose the newly established conservative regimes of which several promoted the idea of a unified Italian political state.

The most famous example is the Carbonari who used armed uprisings. Although many followers were condemned to death, the society continued to exist and caused many of the political disturbances in Italy from 1820 until even after unification.

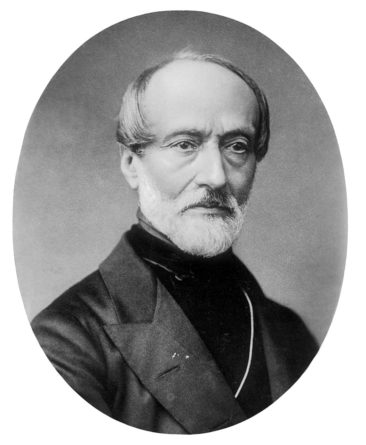

Carbonari member, Giuseppe Mazzini, became one of the most important figures that led to the Italian unification. His group was called “Young Italy”, and this group was one of the first to successfully spread unification ideas across the Italian city-states. The nationalist movement started by Young Italy helped spark more organized and successful revolutions within the Italian city-states.

A skilled diplomat of the kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont named Camillo Benso di Cavour led Sardinia-Piedmont and many other northern Italian states to unite against Austrian control. Through his diplomacy skills and the decisive battles of Magenta and Solferino, Austria recognized the independence of the northern Italian city-states and they all united to form a larger northern Italian state, ruled by Sardinia-Piedmont’s king, Victor Emmanuel II.

In southern Italy, a military man named Giuseppe Garibaldi led several revolts for unification using guerilla warfare, in which a small mobile group of nontraditional civilian soldiers uses typical military tactics to defeat larger legions of soldiers. These revolts proved successful, and following the revolts, the southern states (such as Naples, Lombardy, and Sicily) annexed themselves to Sardinia-Piedmont under Cavour and Emmanuel II’s influence.

Later in 1861, Italy was declared a united nation-state under the Sardinian king Victor Emmanuel II.